We often speak of Japanese martial arts (budō) as a “way,” especially when we want to highlight just how noble and spiritual our activity is. And everyone knows that dō—the “way”—isn’t a road for cars, but a way of life, a journey toward mastery, a movement toward higher goals, the realization of human potential...

I’ll use a capital W here to distinguish this Way from the ordinary kind.

But does it really need to sound so mysterious or uplifting?

What does Way actually mean in practical terms? How does it connect to our everyday training or our everyday life?

At a social event, I once met a young man who told me that he had practiced Aikido for about five years, but eventually stopped “because it was always the same.”

That’s a perfect observation.

It’s also a bit like saying, “I stopped playing piano after five years because it was always the same.”

It’s a sweet and common misunderstanding worth exploring.

Limited Tools, Infinite Depth

Aikido is a tool for human development—beautiful, versatile, complex, and deep. But all that richness is discovered through a very limited set of tools.

Training usually starts with a warm-up and often ends with breathing practice. We train a handful of basic attacks and techniques. We alternate between the roles of uke (the one who attacks and receives the technique) and tori (the one who performs the technique). Day after day. Year after year.

Of course, basic techniques offer endless variations and ways of practice. And the teacher should always look for ways to keep training fresh and help students discover new aspects of the art.

But that, too, has its limitations—a large part of Aikido practice is simply repetition, just like in other martial arts, sports, music, or painting.

The Progress at the Beginning

This group of beginners has been practicing for a month now, and they’re loving it. Every movement and technique is a new mystery to explore. Their teacher just showed them iriminage for the first time, and now they’re working in pairs, trying to connect familiar steps into an unfamiliar technique.

They spin in all directions, get stuck, talk it through, try again… Frustration comes and goes—then comes excitement. After fifteen minutes, most of them are somehow managing the form, and their eyes are glowing with joy.

In those early months, beginners make huge leaps. Everything is new, their interest is fresh, and they improve with every move. They’re like adventurers exploring a strange new land, one with its own physical laws. Aikido is fun and exciting1.

When Nothing Seems to Happen

After about a year of practice, these beginners become “intermediate” students. They’ve learned lots of techniques, and training may start to feel routine. Time passes, the classes start to blur together, and the initial spark may fade. Aikido is no longer new; it might even feel boring.

This is an easy moment to quit.

But those who continue for another month or two may discover that their practice, quite static before, becomes more and more fluid.

Familiar techniques become fun again, full of satisfying challenges:

How do I bring dynamic movement into everything, even the complex forms?

How can I fall more freely?

Aikido becomes new again.

The Frustrating Feeling of Getting Worse

Ondřej is one of the beginners we met at the start of this article. It’s been six years and he’s enjoyed the journey and earned his black belt recently.

That means he now roughly handles all the basic techniques and attacks in Aikido curriculum.For a while, he seemed rightly proud of his achievement. But lately, something’s been bothering him.

“What’s going on?” his teacher asks after class. “Is something wrong?”

“I don’t know. I feel like nothing works. I have a black belt—I thought I had learned something by now. But now I’m getting stuck on even the most basic techniques. I can’t do them right.”

“That’s great!” his teacher laughs.

Ondřej frowns.“What’s great about it? I feel like I’m back at the beginning. Is it even worth continuing?”

This is an important—and fragile—moment. It would be easy for Ondřej to walk away from Aikido right here.

By practicing, his perception has grown, and he’s starting to sense that what was “good enough” a year ago no longer satisfies him.

He feels that something more is possible—and that’s actually a reason to celebrate. But the feeling is frustrating.

The funny thing is, Ondřej is still practicing well. This “decline” is a subjective feeling.

The teacher’s task is to help him understand that this phase is necessary for further growth.

To put it simply: Ondřej has reached a certain level. To move beyond it, his practice has to change. He’s earned his black belt. He knows many techniques. He’s starting to understand the principles that guide the practice.

If he persists, he’ll see that within the same techniques, there’s room to deepen their quality. That he can shift not just how he moves, but how he relates to his partners.

The techniques stay the same, but he keeps growing.

After this short phase of frustration, something new will emerge. Aikido will once again feel fresh and exciting as it once did.

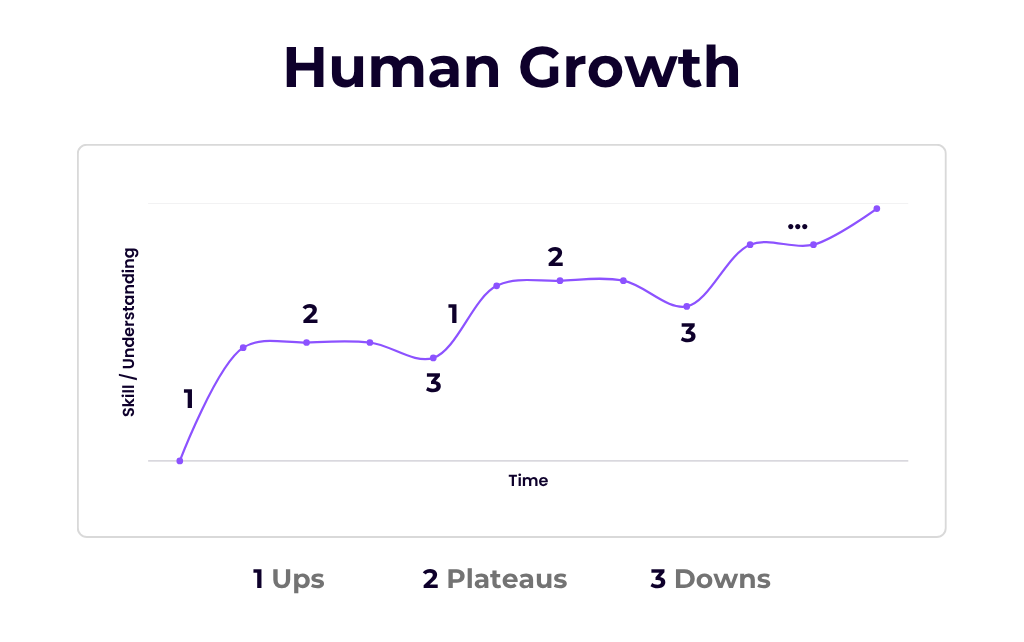

The Waves of Growth

Growth—in Aikido and in life—doesn’t happen at a steady pace.

It moves in waves, usually like this:

1. The Rise – Everything’s new, and every movement feels like progress.

2. The Plateau – Practice feels repetitive, but we’re quietly building strength and skill for the next step.

3. The Dip – What used to work starts falling apart, and the new way doesn’t work yet.

1. The rise again – After a breakthrough, a better quality appears, and new possibilities open up.

...and so on, the loop is infinite.

In Case We Keep Walking

And now we come back to that misunderstanding from the beginning of the article.

If we leave Aikido—or any long-term discipline—the moment it stops being exciting, or when it feels like we’re getting worse, we’ll never move beyond that point.

Even if we find something else and start afresh, it will also eventually become repetitive, boring, or difficult.

We don’t hear much about this in our culture. In ads and on social media, everyone’s always happy and instantly successful. In sports broadcasts and concerts, we only see the high points, the victories, the perfect moments of our idols.

We don’t see the years of their daily effort, sacrifice, disappointment, doubt, and injuries.

Few people talk about the reality, which is that any Way worth walking has not only joy and inspiration, but also hard times, weariness, and frustration.

The purpose of the Way isn’t to entertain us constantly; it rather offers us a structure to support our development and gives us a mirror in which we can see ourselves.

The Tools Stay the Same — We Change

The tools of the Way don’t really change. We change. We use the same tools in new ways, and they take us to new insights and new experiences.

The means of the Way are limited. Our growth is not.

It’s us who is important. Our practice, our curiosity, and our awareness enable us to walk the Way. They carry us over beautiful ridges and through deep valleys of insight.

The trick is to learn

to enjoy not only the sweet moments of progress, but also those stretches where everything feels the same,

to find value even in the moments where we struggle—because it’s in those moments that we grow the most,

to find beauty in every step,

and to keep walking.

That, I think, is good advice for any Way, whether it’s martial arts, music, career, relationships, parenting, or just… life.

Wishing you a good journey.

The phases of growth described above are inspired by the book Mastery by American writer and Aikidoka George Leonard. I really recommend it.

If only we, the advanced practitioners, could still learn this way, even after decades of training...

Dear Martin, thanks for this beautiful writing. Let me add two things:

My personal impression is that there is a common misconception about the word "way". Most of the times it is too literary understood as a way leading from point A to point B. But it can also be understood as a way being. A certain way of acting and living - without a starting point and an end point (mastery or whatsoever). I think of Do more in the letter interpretation. Learning something like Aikido is about learning to take circumstances with a certain kind of mindset.

The second addition refers to art. In which way can Aikido be an art? I think there are two ways of understanding this. The first is the notion that visual arts like painting create structures in space - in certain artistic ways. Music in this concept is a structure in time. Aikido in this notion is indeed like dancing. It is a structure in space AND time.

The other idea I have is about perception and feedback. When i draw or paint in the beginning I am oriented towards the model or the scene I see. But over the time I am redirecting my attention to what I see on the paper. Trying to amplify what I painted. So for me art is about perception and feedback - some kind of closed loop. The same can be said about Akido - therefore I call it an art.

Thank you, keep on writing. Best, Wolfgang