Back when I was just starting Aikido, I attended a seminar with the French teacher Chassang. As this old gentleman explained the principles of Aikido, he began with the concept of shisei—proper stance or posture.

I found this puzzling. The other principles on his list made sense—I knew we had to enter (irimi), strike (atemi), or turn (tenkan). But why was shisei at the very top? As a young karate practitioner, I was familiar with many stances, but I had never considered the stance itself to be a fundamental principle. Why such emphasis on it?

Over the years, I’ve learned a thing or two. And today, I feel that shisei is not just the first principle but, in many ways, the foundation from which everything else emerges.

Posture as a Body Structure

From a purely physical perspective, posture is about body structure. Bones provide support, joints and ligaments connect them, and muscles wrap around them to create movement.

If this structure is well-aligned, the body is balanced, strong, and functional. Movement becomes free and natural—we can enter, strike, turn, unbalance a partner... Every other principle can work.

But if the structure is off, everything starts to collapse a little.

Natural Posture

Let’s simplify things and say the body has two types of muscles: stabilizers and movers.

(Deep) Stabilizers are slower and more enduring muscles. Their job is to support the body’s structure and keep you upright.

(Superficial) Movers are faster muscles designed for movement.

When we just stand, the stabilizers should be doing most of the work, while the movers remain mostly relaxed. The bones settle naturally into the joints, and the tendons and deep stabilizers hold them together. The body stands with ease, as it’s naturally designed.

This structure provides a solid base for movement, which the movers can generate. From this natural stance, we can move in any direction with ease.

When you see someone standing like this, nothing seems remarkable about it. But that’s the point—there’s no magic here. Little kids, around 2-3 years old, stand exactly like this—naturally and effortlessly. And when they need to, they can be surprisingly strong or fast.

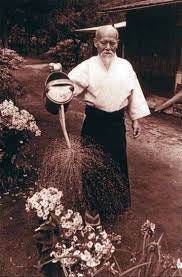

A Picture Worth a Thousand Words

Take a look at this photo of the founder of Aikido. Looks nice, right? Now, take another look.

You’re looking at an 80-year-old man, calmly pouring water over flowers from a 5-10 kg watering can, arm extended, while his body remains effortlessly upright.

Could you do that? Even at 80? 😉

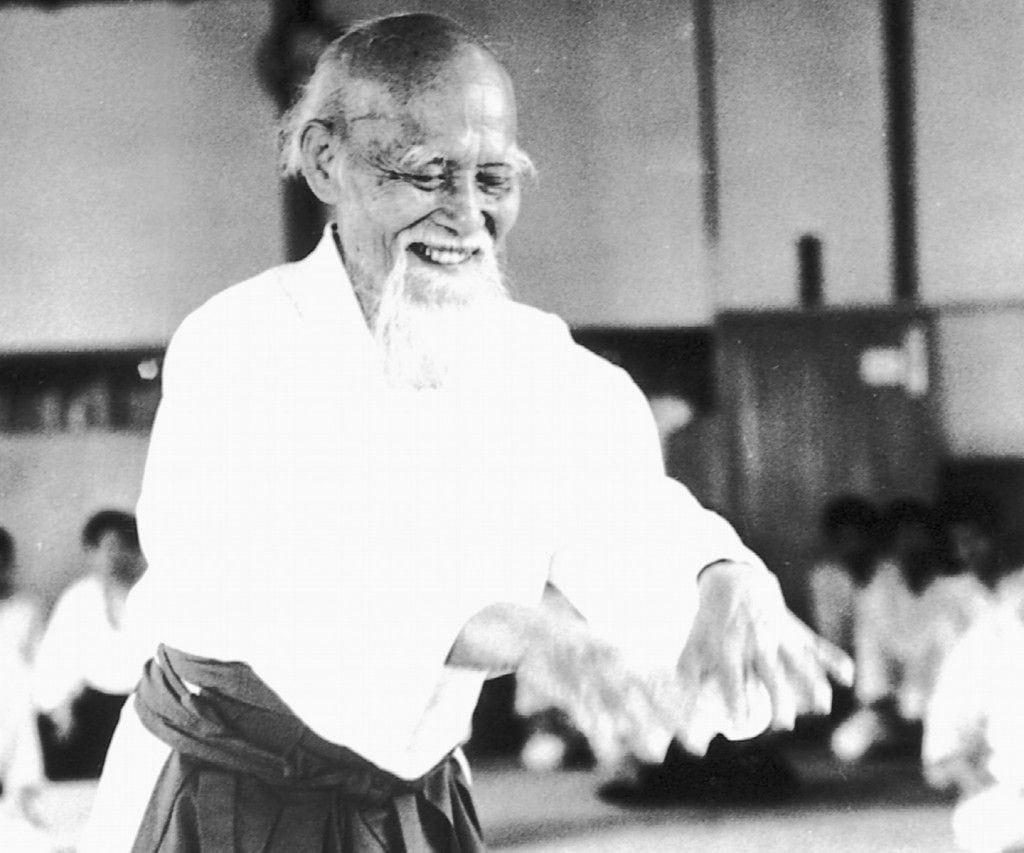

For other examples of a natural posture in martial arts, you can observe how Muhammad Ali moved so relaxed and upright, how top sumo wrestlers stand calm and stable, or how Kung Fu Panda fights with ease.

Sure, You Can Force It

Of course, posture can be held by force.

Many of us have forgotten that stabilizers even exist and rely solely on movers to "hold" our posture. This leads to constant tension—muscles that should create movement instead restrict it.

This happens when someone "puffs up their chest" or "makes big shoulders" to look strong. It may appear powerful, but it’s actually stiff.

And yes, it’s also possible to practice Aikido like this. If someone memorizes the exact form of a technique and powers through it with sheer muscle strength, their technique can still be effective or at least painful.

I recently came across a video on the web—a big, strong guy slamming a smaller guy into the mat with full force. The video title said it was Aikido, and the techniques were recognizable. It looked strong—after all, the guy was tensing every muscle at once.

Not the first time I’ve seen this. Won’t be the last. I shrugged and closed the video after ten seconds.

These kinds of clips get tons of likes—raw power and macho displays grab attention, unlike neutral posture and natural movement, which are far less flashy.

But Strength Has Its Limits

Of course, we use our muscles when we stand and move. And we should exercise to activate and strengthen our muscles in a balanced and interconnected way.

But using excessive force in techniques leads to two issues:

The techniques cannot become more efficient, because being too strong, we don’t feel possibilities where we can unbalance the partner more easily - we just force what we want instead of feeling what the situation needs.

If we use only movers in our practice, stabilizers become lazy and stop doing their job.

Over time, this external strength-based approach runs into problems because Aikido is a lifelong practice… and the external strength of movers declines with age. At some point, all that remains is a worn-out body, with no internal structure to support it and no energy to rebuild it.

If that’s what someone wants, fine. But there’s another way.

The Way to Natural Posture

How can we cultivate the natural posture in our daily training? It’s simple: the key is relaxation and vertical alignment.

Ever had a teacher tell you to “relax your shoulders” and “stand upright”? We hear it all the time, don’t we?

That’s exactly it!

When someone says “relax your shoulders”, they’re inviting you to release unnecessary muscle tension so your body can naturally align itself vertically.

And when someone says “stand upright”, they’re reminding you to align your body vertically, allowing the unnecessary muscle tension to relax.

When these two things happen, the body holds itself together—not through external muscle force of movers, but through its internal structure and deep stabilizers. And at the same time, it remains free to move.

This creates relaxation and ease—the feeling we’re looking for.

This also helps us find balance between two extremes in Aikido (and life):

Over-rigid, tense posture in the name of strong or precise technique.

Over-relaxed, floppy posture in the name of smooth, flowing movement.

I know—it’s easier said than done. And yes, it’s a bit more complicated because sometimes we need to wake up the deep stabilizer muscles, and that takes time.

The good news is that we can keep improving our posture our entire life, and Aikido can help with it.

And here is how to do it practically:

If we want to develop natural posture and movement, the most important thing is awareness.

During training, we need to be aware of our balance, unnecessary tension, or lack of tension. Only when we can feel our bodies can we start improving our posture (and everything else) through practice.

To achieve this, we need to slowly train at least part of our practice so we can actually sense what’s happening in our movement.

Attitude towards Practice, Attitude towards Life

Now, when we know the possibilities, it’s up to us to choose our path.

What are our priorities in the practice?

To focus on building a natural, relaxed, and consistent posture?

or

To have a fast, powerful technique, throwing our partners at all costs?

Have you ever asked yourself this? Because the way we approach our training shapes the kind of attitude we build—in Aikido and life.

And of course, the way we train shapes the way we live. The physical posture mirrors psychological attitude, and psychological attitude reflects physical posture.

Thus, our physical posture in training conditions our internal attitude towards life.

Some people use force against every little challenge that comes their way. Others collapse under the smallest difficulty.

And then there are those who stand upright and move through life with lightness and ease.

Which one do you want to be?

All these things are ever-present in Aikido, but paradoxically, I was exposed to them in Tai Chi. A big thank you to my friend Jan Pletánek, a Tai Chi teacher, for introducing me to the possibilities of building human posture from the inside.

Martin, thank you for this topic. How to be relaxed and firm at the same time is my topic since I started Aikido.

Shizentai